Twenty years on, and the Harry Potter series is still leaving its mark.

It’s a cultural phenomenon spurred by a book series about a magical school. What’s next for the Harry Potter franchise?

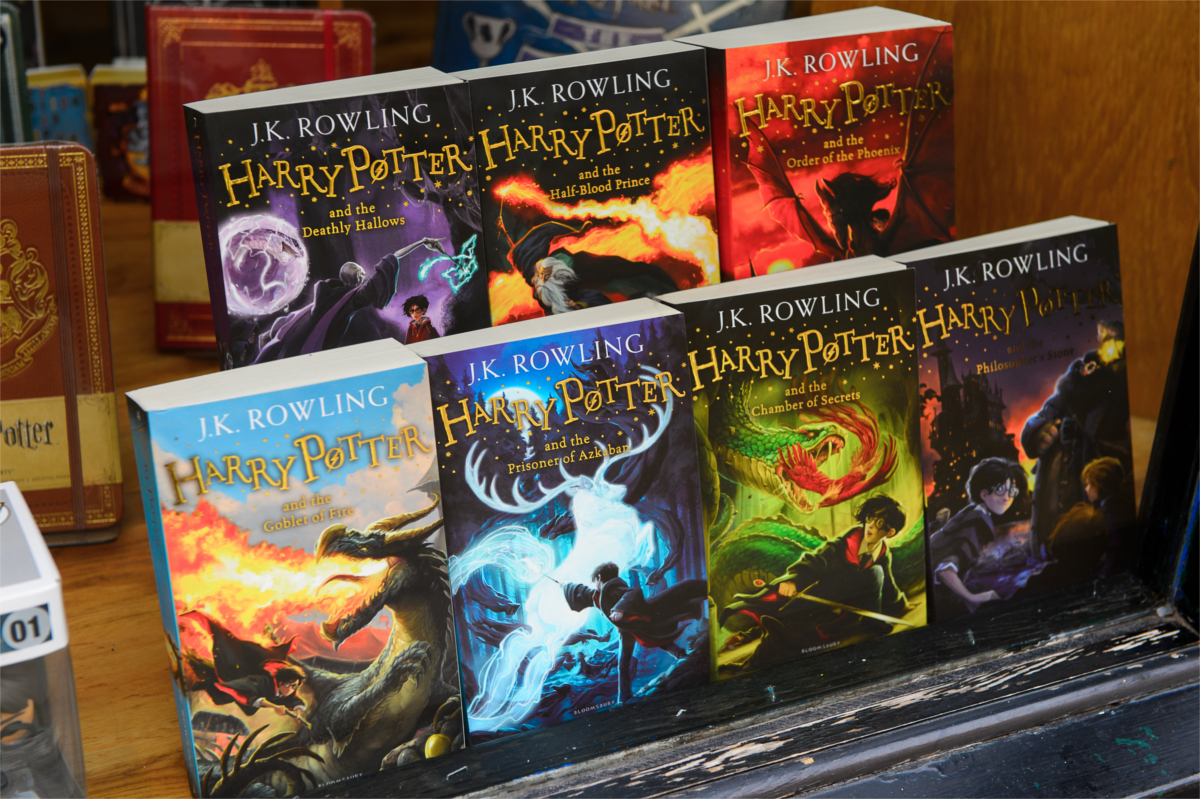

Published in 1997, the original Harry Potter book series is already taking on a faint tinge of nostalgia. Harkening back to a time when cell phones and the Internet were still new and exciting innovations, the series seems steeped in the past, with stories of children running around a castle, writing with quill pens instead of on laptops, and trips to big banks to take out your money rather than the simple ATM.

Twenty years since Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone hit the shelves for the first time, the world has rapidly changed. But it has never quite outgrown Harry Potter. Why is that?

Firstly, it manages the impossible feat of being a book series that appeals to both children and adults. Oftentimes, books written for children are simplistic to the point of being unenjoyable for adults to read. The language is too basic, and the plotlines often involve characters going through things that adults can barely remember going through. The only time most children’s books are read by adults are at bedtime, when parents and kids share the stories together.

And in reverse – books written for adults can be too complicated or inappropriate for children to read and enjoy. Who would want their children to read Fifty Shades of Grey? Even though children are starting to consume the same media as adults earlier and earlier, there is still an awareness of age-appropriate material.

But Harry Potter bypasses all of that, offering the perfect mix of moral complexity and the pure joyfulness of a fantasy world where people can wave a wand and make the perfect cup of tea. And with the growth and popularity of the book, publishers have released editions with new art covers which are ore sleek and sophisticated design to appeal to it’s mass ageing audience.

It fuels the real world with a sense of magic, mixing both the fantastical and ordinary with ease. Although the children in the Harry Potter universe attend a boarding school in the remote Scottish highlands, they get there from King’s Cross station, one of the busiest stations in London. These may be children with magical powers, but they still get detentions and try to rebel against strict teachers.

Another reason for its initial popularity in Britain is its format – Harry Potter joins a long-standing tradition of British boarding school novels, a popular genre in a country where children often leave home at the age of eight for education’s sake.

- The Palace Theatre London, Harry Potter and the Cursed Child. Photographed by S Kozakiewicz. Image via Shutterstock.

Although there are certain elements of Harry Potter that are undeniably British, the series’ popularity transcends cultural and language barriers – the moral struggles the characters face are universal enough to capture the attention of readers everywhere, from Seoul to Stockholm, Malaysia to Moscow. The books have been translated into sixty-seven languages, making it one of the most translated pieces of literature in history. Fun fact: the first book was even translated into Latin and Ancient Greek, for all the Classics-mad Potterheads out there, making it the longest published work in Ancient Greek since the third century AD.

Even so, when the books were being released, fans couldn’t wait the several months translations would take, and the fifth book became the first English-language book to top France’s bestseller list. The fervour the books garnered was unprecedented, and no other series has had quite as much widespread appeal.

And fans haven’t just passively responded to that mix of familiarity and fantasy with great enthusiasm. Harry Potter fans, affectionately referred to as ‘Potterheads’, have done everything from puppet parodies to entire conventions with names like ‘LeakyCon’ and ‘Infinitus’. 2009 saw the release of A Very Potter Musical, an independent production by the University of Michigan’s Starkid Productions, which turned the story of Harry Potter into a comedic musical theatre fest. The books have even impacted scientific progress, with several new species being named after Harry Potter characters and elements – including the spider Eriovixia gryffindori and the crab Harryplax severus. The amount of fan involvement is unparalleled.

- Harry Potter Dragon Walk at Universal Studios Orlanda, Florida. Photographed by P Miami2you. Image via Shutterstock.

And that uniqueness of reaction is what made it take on a life outside that of the scrawny, dark-haired boy in the original series.

Although J. K. Rowling has stated she won’t write any more books of Harry Potter’s story, the wizarding world is still alive and well. She turned the world’s eye on Harry Potter’s children with Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, a two-part stage play (meant to be viewed on the same day, or over two consecutive evenings) premiering in 2015. The play features Harry Potter as a side character, but the focus is on Albus, Harry’s son, and Scorpius, the son of Harry’s school rival. It had a warm welcome to London’s theatre scene, receiving a record-breaking nine awards in the 2017 Laurence Olivier Awards. A version of the script was also released to fans ravenous for new content – possibly the last official written piece of work featuring the character they had grown up with.

Big businesses have seen the benefit of latching onto Harry Potter’s enduring popularity. The Universal Studios Wizarding World of Harry Potter theme park opened to staggering success – six months after the opening in June 2010, the park had lifted Universal’s full-year attendance by 20 per cent.

To appeal to an audience of children more accustomed to watching Netflix than sitting down with a book, Warner Bros distributed Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them – starring Newt Scamander, the fictional author of a Harry Potter textbook of the same name, it made over $810 million at the box office, and was the first film in the Harry Potter realm to win an Academy Award. There are plans for two more films in the same timeline, thereby cementing the fact: the Harry Potter universe has extended far beyond the titular main character, stretching both into the past and the future.

And it may not even end there. Although Newt Scamander’s story might be concluded in a few years, there’s infinite potential within the Harry Potter universe. J. K. Rowling’s dedicated web resource for content relating to the series, Pottermore, has information about the ten other wizarding schools that exist around the world, with detailed backstories about their origins and operations. Fans are also always eager to find out about the fates of the other side characters in the original series, and the success of Cursed Child speaks for the fact that people are even interested in characters they’ve only spied briefly. The world is so complex, it’s impossible to truly gain an impression of all of it, which is something quite remarkable- the world has extended beyond even the creator’s scope. It would’ve been impossible for J. K. Rowling to truly understand the enormity of what she was creating in small cafes in Edinburgh, rocking her daughter to sleep.

And if the studios continue to tap into that potential, it could be a while before we truly see the end of the Harry Potter phenomenon.

So although the story of Harry Potter has ended, the world he inhabited will live on. For possibly a very, very long time to come.